Key Points:

- What is patellar tendinopathy? (4)

- Patellar tendinopathy is an injury to the patellar or quadriceps tendon that usually occurs gradually over time and worsens in intensity with more challenging activity (walking vs. squatting vs. jumping).

- It is generally thought of as an overuse injury that occurs in athletes that expose their patellar tendons to excessive stress.

- What is the prevalence of patellar tendinopathy? (4)

- Most common in men aged 15-30 years old.

- Commonly presents in group sports such as basketball, volleyball, athletic jump events, tennis, and football, which require repetitive loading of the patellar tendon.

- What is the clinical presentation of patellar tendinopathy? (4)

- Pain is usually localized to the inferior pole (bottom) of the patella.

- Pain generally occurs with activities that require increased demand on the knee extensors (quads), especially with activities that require storage and release of energy in the patellar tendon (jumping).

- What are the risk factors for developing patellar tendinopathy? (3)

- Greater total training volume and greater total amount of matches played

- Spikes in training volume (increase in weekly playing volume)

- What is the treatment for patellar tendinopathy? (2,3,4,8)

- An initial period of unloading and modification of training followed by progressive strengthening of the quadriceps and patellar tendon.

- An initial period of unloading and modification of training followed by progressive strengthening of the quadriceps and patellar tendon.

Patellar Tendinopathy Basics and Statistics

Patellar tendinopathy is one of the most common overuse injuries I see with athletes in the weight room. Patellar tendinopathy is more commonly known as "jumper's knee" and is mainly described in our medical literature to occur in sports that require a lot of jumping (2, 4).

However, weight training in the gym with lifts like squats, olympic lifts, lunges etc. place a good deal of stress on the patellar tendon and because of this the patellar tendon can sometimes become painful and limit someone's training. Next to patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), jumper's knee is the second most common overuse knee injury I tend to treat.

I wanted to make a comprehensive review of this common condition and how we can go about treating it, with specific focus on helping people who want to get back to the weight room. So here we go!

What is Patellar Tendinopathy? (4)

Jumper's knee is an injury to the patellar or quadriceps tendon. It generally does not occur with a single traumatic event. It usually occurs gradually over time and worsens in intensity with increasing activity. It is generally thought of as an overuse injury that occurs in athletes that expose their patellar tendons to excessive stress. As with most overuse injuries, the development of jumper's knee may also include insufficient recovery time between bouts of exercise.

A combination of excessive training stress combined with insufficient time for the tendon to remodel after training can lead to this condition. This results in portions of the tendon to become "pathologic" over time.

Side Note: Cook and Purdam describe this as a "doughnut" phenomenon (or donut if you live in the New England area). Basically, if you stack up a bunch of donuts one on top of another, the structure is still sound despite still having a hole right in the middle. When we have a pathological area of the tendon our rehabilitation focuses on strengthening the non-pathological tendon areas and we can still have a strong and functional tendon despite these pathologic sections (6).

What is the Presentation of Patellar Tendinopathy? (4)

So there are a lot of different knee diagnoses out there. What can we expect to find in folks with this condition?

- Pain is localized to the inferior pole (bottom) of the patella

- Pain occurs with activities that require increased demand on the knee extensors (quads)

- Pain occurs with activities that require the knee extensors to store and release elastic energy in the patellar tendon (jumping and plyometric activities)

- Tendon pain occurs instantly with loading and usually ceases almost immediately when the load is removed

- Pain rarely occurs while resting

- Pain may improve with repeated loading (the “warm-up” phenomenon) but there is often increased pain the day after

- Pain is generally consistent with the demands of the activity (For example, more load in a squat, more depth while squatting, more intense jumping variations, longer duration of knee intensive activities often equate to increased pain levels)

Differential Diagnosis

People with patellar tendinopathy can also have pain with prolonged sitting, squatting and stairs but these symptoms can also be associated with other types of injuries like patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS). PFPS is generally a more vague knee pain somewhere under or around the patella and not just localized to the patellar tendon.

What is the Prevalence of Patellar Tendinopathy? (4)

So where do we tend to see most patellar tendinopathy cases? Patellar tendinosis

- Is more common in men

- Is most common in the age group from 15 - 30 years old

- Commonly presents in group sports such as basketball, volleyball, athletic jump events, tennis, and football, which require repetitive loading of the patellar tendon

At What Stage in Life Does Patellar Tendinopathy Develop?

What's interesting about patellar tendinopathy is that is seems to develop mainly during adolescence. Basically, most folks who acquire patellar tendinopathy have it before they go through puberty and less folks go onto develop it afterwards despite playing sports that place high demands on the tendon like volleyball. (17). In other words we tend to develop patellar tendinopathy less frequently after hitting puberty unlike other forms of tendinopathy like the achilles. (17)

How Long Does Patellar Tendinopathy Last?

Patellar tendinopathy can also be a real problem because many people can't seem to rehabilitate fully enough to get back to sport after getting injured. Cook et al. found that more than one third of athletes presenting for treatment for patellar tendinopathy were unable to return to sport within 6 months, and it has been reported that 53% of athletes with patellar tendinopathy were forced to retire from sport (4).

What are the Risk Factors for Developing Tendinopathy?

So we already discussed that jumper's knee is largely a condition of overuse and can occur if bouts of exercise are performed without adequate recovery to allow tendon remodeling. Here are some risk factors for predicting who ends up going on to experience problems:

- Increased weekly training sessions (3)

- Greater total training volume and greater total amount of matches played (volleyball) (3)

- More weight training sessions per week (3)

- Decreased hip extensor strength (glutes, hamstrings etc.) (3)

- Decreased hamstring and quadriceps flexibility (2)

- Patellar tracking issues (3)

- Increased knee flexion (bending) and decreased hip flexion (bending) during jumping and landing tasks (3)

- Stiff (minimal bending at hip and knee) landing pattern with minimal ground contact time during jumping and landing (3)

- Sport specialization (playing 1 sport vs. many) (3)

- Greater jump performance (3)

Side Note: Athletes who are better at jumping are more prone to develop tendon problems. The best athletes may know how to best utilize the elastic nature of tendons to transfer power. Because of this they may simply take more stress through their tendons and are more prone to tendinopathy. (3) Also remember that folks with tendinopathy also have more healthy tissue which may improve jumping ability as well.

Anatomy Basics

Before we discuss what jumper's knee is, we have to talk a bit about the anatomy of the area. The patellar tendon is actually a ligament that attaches the patella to the tibia of our knee. The patella also attaches to the quadriceps tendon which attaches to the quadriceps. With the aid of the quadriceps this system helps to extend (straighten) the knee and control landings from a jump and the descent of a squat.

Image Source, Attribution: BruceBlaus. (18) License: CC BY https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0

Patellar tendinopathy usually occurs right below the patella but can also occur less commonly at the attachment of the patellar tendon and tibia (tibial tubercle) or in the quadriceps tendon itself.

What Causes Patellar Tendinopathy? (4)

"Itis" vs. "Osis"

Jumper's knee was formerly known as patellar "tendinitis". The "itis" portion of tendinitis generally refers to an inflammatory condition. We used to think that the tendon becomes painful because of inflammation in the area. What we've found over the course of time and with research is that this condition is generally not inflammatory in nature but more of a degenerative (wear and tear) condition (2). Basically, with excessive stress over the course of time the tendon attempts to adapt to the stress of training. The tendon goes through changes because of this stress and can sometimes become painful. This is referred to as "osis" or the "opathy" found at the end of patellar tendin-opathy.

How Tendinosis Occurs

Tendons perform similarly to springs in the sense that they store and release energy. High performance activities like jumping and weight training require the patellar tendon to store and release energy just like a spring does (4). The better tendons store and release energy the better we perform these activities (4).

If we perform too much tendon intensive movement, or have insufficient rest between bouts of tendon intensive activity we don't allow the remodeling process that normally occurs after stressing a tendon (2). This can induce pathology and changes in the tendon's mechanical properties known as tendinopathy (2).

A tendon with tendinopathy has sections within it that look yellow-brown under a microscope as opposed to it's normal white color. The collagen make-up of these pathological sections of tendon also become disorganized in comparison to it's normal longitudinal alignment. (2)

What's also important to understand is that tendons with tendinopathy actually have MORE HEALTHY tissue than a normal tendon. (16) What this means (atleast in the achilles and patellar tendons) is that as a tendon is exposed to excessive training stress it adapts to add more healthy tissue as well as additional pathological tissue. This results in a thicker tendon with more net healthy tissue than compared to a tendon without tendinopathy. (16). This is an important distinction because the creation of tendinopathy in our bodies could potentially be seen as a positive adaptation, especially given that athletes with more tendinopathy tend to display better jumping and sprinting performance. (3)

Tendons with tendinopathy also have something called "neovascularization" which is the growth of new vessels within the tendon (6). Nerves are one of these structures that grow during neovascularization and this increase in neural structure is one theorized reason why patellar tendinopathy can become painful. This tends to make sense given that more neovascularization in the tendon is associated with more pain in individuals with patellar tendinopathy (6). Lastly, having these pathologic changes in your tendon increase your risk of developing pain (2).

What Percentage of Tendinopathy is Painful?

Hold your horses, so having these tendon issues doesn't automatically mean we'll have pain?

No, generally only about 20% of people with radiographic evidence (MRI or Ultrasound) of tendinopathy actually have pain (7). This means that around 80% of people with tendinopathy have no pain at all (7).

In other words, tendons in your body that take stress over time are likely to develop some tendinopathy. We know this occurs in sports where certain tendons are predictably stressed (Think patellar tendinopathy in volleyball or basketball players and tennis elbow in tennis players) (7).

Just because you have tendinopathy doesn't mean that you'll develop pain BUT you will be more likely to develop pain then someone without tendinopathy (7).

I'll repeat this because it's a little confusing. People with tendinopathy diagnosed with an MRI or ultrasound don't always have pain but are at an increased risk of developing pain at some point in the future.

What is Effective as Treatment for Patellar Tendinopathy?

So now that we have the basics out of the way, how do we go about treating patellar tendon issues? Below I've outlined the 6 steps I like to use with my patients and go more in depth below:

- Knowledge About the Diagnosis and Pain

- An Initial Period of Unloading and Modification

- Direct Quadriceps Strengthening and Patellar Tendon Loading

- Kinetic Chain and Sports Specific Strengthening (Hips, Calves, etc.)

- Assessing for and Correcting Mobility Limitations

- Modifying Jumping and Squatting Technique

So let's go ahead and talk about these key principles then huh?

1: Knowledge About Diagnosis and Pain

In order to start the process of rehabilitation we need a bit of information about the condition itself, pain and some expectations during rehabilitation. Lack of knowledge about this condition can set us up for things we call:

- Poor Beliefs

- Fear Avoidant Behaviors

- Catastrophizations

- Central Sensitivity and Chronic Pain

Essentially, lacking knowledge about this type of injury can cause us to have poor beliefs that don't help us rehabilitate. One poor belief may be:

"I don't want to push this injury because every time I do it hurts. Having pain means the area is not healed yet and I should rest until it stops hurting"

A belief like this leads to what's called fear avoidant behavior. If you're fearful of causing more damage or delaying the healing process, you may avoid all exercise that stress the area.

As we'll talk about soon, exercise when dosed appropriately is the most beneficial thing we know of to help rehabilitate these injuries and completely avoiding any stress may prevent you from getting better (2).

A catastrophization is a belief that the situation you're in is far worse then it really is (9). This is another irrational belief that is certainly not helpful for getting out of pain. Here's an example:

"The stupid knee injury will never heal and I won't be able to squat ever again"

In reality, patellar tendon injuries generally do improve over time (2) and there is a good chance you'll get back to the weight room.

You can see how irrational these beliefs are and if they aren't addressed they can spiral out of control creating even more stress and anxiety for your patient. We want to be aware of this phenomenon and address it when you see it.

Geeky Side Note: We know that in people with chronic pain, these negative beliefs or catastrophizations are associated with poor function and worsening pain. However, we aren't sure yet whether the pain led to worsening beliefs or the negative beliefs led to more pain. (9) We do know that educating patients about pain decreases their pain, increases physical performance, decreases perceived disability and decreases catastrophization atleast in the short term. (9) Hopefully it also helps to change our behaviors in a positive way as well.

Lastly, mismanagement of this condition (coupled with poor beliefs like we spoke of above) can lead to prolonged pain that is sometimes out of proportion to the actual damage present with the injury. We call this central sensitivity (9). Basically our nervous systems get extra sensitive, out of proportion to the actual state of the injury.

Pain Science Side Note: Central sensitization is not the same as an athlete continually training with too much volume, poor technique, poor movement and a lack of a solid rehabilitation program. In this case our athlete is continuing to irritate the patellar tendon and reducing the ability to adapt and heal. Central sensitivity is perpetuated pain (coming from increased sensitivity of the brain and spinal cord) in the absence of offending stress to further damage the tendon (9). Just keep in mind that continued poor behavior might actually lead to more sensitivity.

Lucky for us, we can avoid most of this with some good old advice and starting off on the right foot.

How Long Does it Take for Pain to Go Away?

What's important to understand is that this is a condition that does actually tend to get better with the right treatment and won't necessarily haunt you for the rest of your life (2).

That being said, tendon issues typically take a long period of time to get better. In our medical literature, most successful rehabilitation programs last 8-12 weeks (although that doesn't mean symptoms completely resolve by the end of the program) (2). However, it is common for these issues to take 6 or more months to resolve (4). A research study by Bahr and Bahr found that only 46% of people reported no pain and full return to sport training 1 year following a strength based rehabilitation program (4).

The take home point is that it's normal for the process to take a long period of time to resolve. They can always resolve more quickly but this isn't always the case so be prepared for the long haul.

Another concern of athletes with patellar tendinopathy is the tendon rupturing (tearing completely). Lucky for us, rupturing the patellar tendon is not common and with proper rehabilitation shouldn't be a major concern (4).

The next topic to understand during rehabilitation is pain. Patients need to be set up with a basic understanding of pain so they can progress forward.

Pain is a protective mechanism and exists to keep us safe. (Click HERE for a video to help understand this better) That being said, once you have pain your body is trying to tell you not to do anything stupid to let this injury recover. The other important concept to understand is that pain and injury are not completely correlated. When you get an injury, the area gets sensitive (because your body is trying to protect you). Therefore movement and loading may hurt, but if the loads are kept at the right dosage, no damage is caused. (10)

Side Note: In most of our patellar tendon rehabilitation research, pain is kept between a 1 and 5 out of 10 on a 0-10 pain scale during physical therapy exercises (2). In some of the studies the criteria for advancing an exercise is when the exercise is no longer painful (2). The idea here is that if we aren't provoking atleast some pain, the exercise may not be hard enough to cause progress (2).

The next thing to understand is that the stress of exercise and loading your painful tendon is actually what helps the tendon heal and get out of pain (2).

The last point to understand is that tendons generally respond well to heavy loads (4). More recent research coming out about patellar tendon pain and physical therapy is showing that heavy loading is a beneficial treatment for these folks (5).

Side Note: An over-reliance on passive treatments such as ultrasound, laser and manual therapies can also keep athletes from progressing over time. Our research shows us that it's loading we know to be most effective for this condition. This is important because many patients have a strong belief in passive therapies and we need to ensure they know passive treatments are not the gold standard treatment. (4)

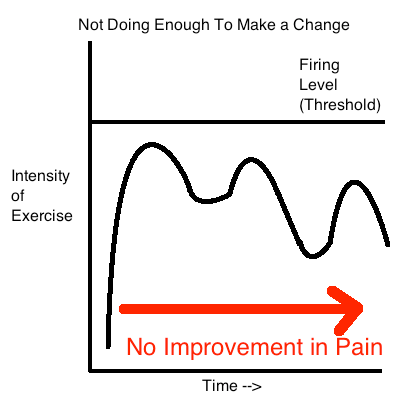

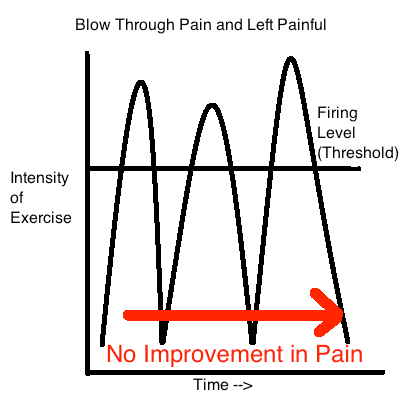

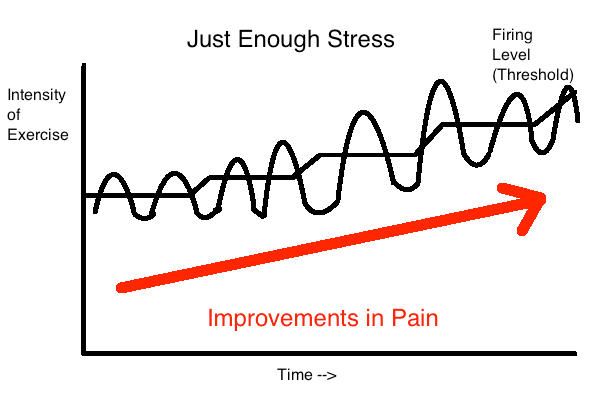

So in patellar tendinopathy, exercise ends up being a double edged sword. If we apply too much stress to the tendon it can potentially make the situation worse. Too little and the same situation may occur.

In both of these examples we aren't applying the right dosage of pain and this behavior can make the pain stick around or worsen (4, 8).

In the last example we have an athlete who is working with their pain. They load their patellar tendon with just the right amount of exercise to cause improvements in pain. As the pain improves with time and exercise, they progress the difficulty of training as well to continue making progress. This is key to rehabilitation. (Click HERE for a more thorough explanation of this phenomenon)

So how much pain is acceptable during rehabilitation? As I said before, our research is a bit varied in this regard. Some studies allow up to a 5/10 on a 0-10 pain scale during exercise (4). Some are lower (4). Some studies also recommend pain levels returning to baseline 24 hours following exercise (4). With this research in mind my general recommendations are:

- Pain should be kept at or below a 3/10 during physical therapy exercises

- Pain should return to baseline levels 24 hours following a therapy session

- Pain or exercise tolerance should be improving from week to week and month to month

Keep in mind that these are not hard and fast rules. Some people may be able to push into more pain and make progress. Others may have to back off a bit more than others. Lastly, keep in mind that pain is a dynamic process that changes day to day. Trying to quantify your progress on a daily basis is just like looking at the scale every day to figure out if you're losing weight. It takes time and will fluctuate. This is normal.

2: An Initial Period of Unloading and Modification

Now this may be a no-brainer for most people but it is a commonly missed step for rehabilitation of jumper's knee. We know from our medical literature that if we don't modify our activities with patellar tendinopathy often times the pain can persist (4, 8). We also have some research to indicate that if we try to simply apply a strength program to the tendon without modifying our current training or sports routine the outcomes are poor and can even lead to worsening of pain (4).

As we learned on the flip side of the coin, we also don't want to fully unload the tendon. We know this isn't the best plan of attack to return to activities and can lead to weakening of the tendon (2).

However, we will have to decrease the stress of our activities enough to allow the area to calm down and become less painful. In a case study by Silva et. al eliminating all activities that create more than a 2/10 during sports training in addition to adding a strengthening program along with some modification of jumping technique led to an improvement in pain (3). Studies in similar knee conditions like patellofemoral pain syndrome show an initial period of unloading or modification to lead to better long term outcomes then no period of unloading (8).

So how do we modify our athlete's weight training? My general recommendations are to:

- Temporarily eliminate activities that produce pain >2/10

- Temporarily eliminate activities that cause pain to increase 24 hours following training

- Reduce total training volume and or intensity enough to have pain levels return to baseline 24 hours following training

As the pain improves over the course of time we can slowly start leaking back in more training and movements that were previously too painful. Just make sure that when we re-introduce previously offending movements they obey the guidelines outlined above.

3: Direct Quadriceps and Tendon Strengthening

As discussed earlier, a common mistake when attempting to rehabilitate from jumper's knee is avoiding painful movements altogether. Initially it's natural and acceptable to modify exercises that aggravate the patellar tendon like front squats to more hip dominant movements like barbell back squats. This allows us to continue training without irritating the tendon. As discussed above in concept 2, modifications like this can be beneficial when attempting to dose stress to the patellar tendon.

The issue with this strategy is that we know that movements that directly stress the tendon (like a single leg decline squat shown above) work better for rehabilitation than regular squats for rehabilitating patellar tendinopathy (2). We also have research to show that during patellar tendinopathy individuals have substantial motor cortex inhibition of the quadriceps muscle group (4). This is basically a fancy way of saying that the quadriceps muscle is not firing well.

People with long standing patellar tendinopathy can also have large amounts of atrophy (decreased muscle size) of the quadriceps muscle group (4). It makes sense that if the muscle doesn't fire well we need to ensure we get it firing well and restore strength. We can't do this if we substitute all quad dominant movements in the gym to hip dominant movements.

Shifting your entire exercise program to hip dominant movements (deadlifts, box squats, good mornings etc.) may allow you to train without pain but doesn't do much for weak, inhibited quads. It also doesn't stress the tendon to allow it to adapt either. We'll have to ensure we apply some direct tendon and quadriceps strengthening to fully rehabilitate.

What is the Best Frequency of Physical Therapy Exercises?

The frequency of exercise for patellar tendinopathy is our medical literature is somewhere between twice per day and every other day (2). These exercise programs also tend to be progressive in nature. As the tendon becomes more and more resilient, we apply progressively more challenging exercises (2).

What Type of Exercises Should a Physical Therapy Program Consist Of?

At the end of the day, a through physical therapy program should consistent of progressive loading within an athlete's tolerance that eventually works back to sport specific activities. Malliaras et. al have proposed a progressive 4 stage patellar tendinopathy rehabilitation plan to help clinicians in this regard (4):

- Stage 1 Isometrics: Isometric (no movement) knee extension (between 30-60 degrees of knee flexion) for 5 sets of 45 seconds at 70% of your maximum effort. Performed 2-3 times per day

- Stage 2 Isotonics: 3-4 sets of 15 repetitions every 2nd day. Repetitions decrease over time and load increases.

- Stage 3 Energy Storage Loading: Progressive (volume and intensity) jumping, sprinting, cutting activities specific to demands of the sport

- Stage 4 Return to Sport: Progressive exposure to sport specific training drills and competition

Basically if you have too much pain (described as more then minimal or >3/10) during isotonic (exercise with motion) exercises then you start with isometrics (pressing against an immovable object). Once you can tolerate isotonics with minimal pain, you move to phase 2 where you start working towards symmetrical strength between legs.

Once you're showing symmetrical strength in isotonic exercises in stage 2, you can move onto stage 3. (Keep in mind these energy storage exercises should also have minimal pain and your pain levels should return to baseline 24 hours after exercise.) As your energy storage exercises progress to the point where they begin to replicate the sport specific demands of your sport, it's time to progress to more sport specific training and competition.

Also keep in mind that each stage may last several weeks. As stated before, rehabilitation often takes 6 months or more and progression shouldn't be based solely on time but instead on how well the tendon is tolerating exercise.

For our average lifter trying to get back to training in the gym their program may look like this:

Phase 1: Isometric (started when isotonic exercises are too painful)

- Knee extensions against the wall @45 degrees

- 5 sets of 45 second holds at 70% of maximal perceived exertion

- 3x per day

- 1 week in duration

Phase 2: Isotonic (started as soon as tolerated with minimal pain)

- Decline single leg squats 3-4 x 15

- Machine quadriceps extension 3-4 x 15

- Performed every other day

- 6 weeks in duration

- Each week progressing to heavier and lower rep ranges (week 2 sets of 12, week 3 sets of 10 etc...)

Phase 3: Energy Storage Loading (started when tolerated with minimal pain)

- Box jumps 3 x 3

- Running - 15 minutes of 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off interval runs

- Performed 2-3 x per week

- Continue with isotonic exercises

- 4 weeks in duration

Phase 4: Return to Sport (started when energy storage exercises begin to mimic sport activities)

- Slow transition back to regular gym activities

Keep in mind that the exercises selected in phase 3 and 4 will vary greatly based on the person and what they want to return to. For a basketball athlete it may consist of a large variations of jumping, cutting and acceleration drills. For the olympic lifter it may be more explosive lifts like jerks, cleans and snatches.

Side Note: This is a frame work for rehab described in one study. That certainly does NOT mean this is the only way or the best way to treat patellar tendinopathy. However, it makes logical sense and has been used successfully as a guideline for others folks and myself included. I just don't want to make the statement that this framework is the absolute gold standard that everyone needs to follow...

4: Kinetic Chain and Sports Specific Strengthening

When you’ve got an injury it’s easy to focus all of your attention directly at the injured area. Truth is, your entire body moves as a unit and multiple joints and muscles need to work together to complete movements like squats, deadlifts and olympic lifts.

Think of it this way. Let’s say you have a tug of war team with 3 team mates. One is an NFL lineman, the second is a professional soccer player and the third is a marathon runner.

Let’s say your NFL lineman is slacking and not doing his job properly. The soccer player and marathon runner are going to have to pick up the slack. Because of this, the soccer player gets injured. Maybe she wouldn’t have gotten hurt if the lineman did his job properly.

Now let’s say the NFL lineman consist of the muscles around your hip. Let’s say the soccer player consists of the muscles around the knee like the quads and hamstrings. Lastly the marathon runner consists of the muscles around the ankle like the calves.

All of these muscles need to be optimized to normalize the stress at the knee and patellar tendon. Failing to address this whole chain can be a reason why your rehabilitation program fails (4).

Sport Specificity in Physical Therapy

The other important piece to recognize is that your rehab program should start looking more and more like your typical training program over time. This is known as sports specificity (2, 4).

For an olympic lifter, heavy squats and olympic lifts may need to be eliminated from your program initially. As the knee starts to improve you can start to slowly introduce squats back into your program. As these are tolerated we can add in olympic lifts, starting with power variations and slowly progressing towards full squat variations.

For an athlete that performs a lot of jumping (sports like basketball and volleyball) they’ll probably require an initial period of unloading from jumping activities. As the tendon progresses over time you can start slowly leaking in jumping exercises.

Jump Training

Jumping exercises should be progressive in nature, starting with easier variations and progressing to harder variations. A typical progression may look like:

- Double leg jumping --> Single leg jumping

- Less reactive jumping --> More reactive jumping

Here are some progressive jump variations to help you design a program if you're looking to get back to jumping:

You can see how the stress on the quadriceps tendon will advance as we progress towards more challenging jump variations.

5: Assess for and Correct Mobility Limitations

As discussed in the part 1 of this article series people with patellar tendinopathy can also present with hamstrings and quadriceps tightness (2). We also have some medical literature that shows that if you add hamstrings and quadriceps stretching to a patellar tendinopathy strengthening program, the results are better (2).

Use the assessments below to determine if you or your patient has a mobility limitation in their quads or hamstrings:

Mobility for Quads and Hip Flexors

Mobility for Hamstrings

Once you've got a plan to address quadriceps and hamstrings mobility, the next important thing to tackle is ankle dorsiflexion flexibility. Now, if we're lacking ankle dorsiflexion mobility, this can create what's called "dynamic valgus" or "knee in" during squatting tasks (11). Check the video below to see how:

So, tendons are very good at taking stress in alignment with the fibers they are made up of. When we get dynamic valgus we expose the tendon to forces that rotate the tendon along with normal tensile loads. Tendons are generally not as good at handling these rotary forces and the idea is that this can contribute to developing tendinopathy.

Either way, dynamic valgus at the knee is generally a suboptimal way of moving and has been implicated in other knee issues such as ACL injury and patellofemoral pain syndrome. It's probably a good idea to minimize the amount of valgus during jumping, squatting and single leg strength training.

For these reasons it’s important that we assess for ankle mobility limitations and correct them if present. Use the assessment below to see if you have an ankle mobility limitation into dorsiflexion.

If you’ve got a a restriction, here are some of my favorite stretches and mobilizations:

Mobilizations for these restricted areas obviously should be a regular part of your rehabilitation program.

There is a lot of confusion out there currently for how often stretching and foam rolling exercises should be performed. Here are some general guidelines for frequency and duration of mobility:

Stretching (12):

- 60 seconds stretching per muscle group

- 5-7 days per week (the sweet spot is 5-10 minutes of stretching per week)

Foam Rolling (13):

- 60 seconds foam rolling per muscle group

- 3x per week (dunno optimal dosage yet, literature shows longer term improvements with this recommendation)

Mobilizations:

- 10-15 reps performed after stretching and foam rolling

Side Note: If you'd like to read an article going more in depth on flexibility click HERE:

6: Modifying Jump and Squatting Technique

One contributing factor to patellar tendinopathy may be how our athletes choose to move during sporting tasks like jumping, squatting and running (2, 4).

The way we squat and jump affects the amount of stress on the patellar tendon. A few things that increase stress on the patellar tendon (2):

- Increased knee flexion (increased squat depth)

- Increased load (i.e. added weight to the barbell)

- Forward weight shift

- Faster more explosive contractions that require the tendon to act as a spring

- Dynamic valgus at the knee

Let's explore each of these a little deeper.

1: Increased knee flexion

As we descend deeper and deeper into a squat we simply place more and more stress onto the patellar tendon (2). We can easily modify depth of squatting and other knee bending exercises to place more or less stress on the patellar tendon.

2: Increased load

The more external load (weight on the bar) we use during a given movement, the more load on the patellar tendon (2). This is partially due to the amount of quadriceps activity during a given exercise. The harder the quad is forced to work, the more stress goes through the patellar tendon

3: Forward weight shift and knee displacement

This point is subtle but important to understand. The more shifted forward our bodyweight is during a squatting or landing task, the more stress on the patellar tendon. In the image above we have someone landing with more forward weight shift (left image) and someone landing with more backwards weight shift (right image). The cue of "hips back" during landing displaces the weight backwards and reduces stress on the patellar tendon (3):

The same goes for the squat, the more we sit back during a squat, the less stress on the tendon. If you've got a painful tendon, this tends to reduce pain.

Lastly, utilizing a decline board during single leg squats also forces an anterior weight shift (anterior knee displacement as described in the article). This decline also increases stress on the patellar tendon (2).

Side Note: It's important to point out that once you acquire patellar tendinopathy, directly stressing the tendon with decline squats actually produces better results for rehabilitation than single leg squats without a decline (2). This points to the importance of directly stressing the tendon for rehabilitation.

4: Faster more explosive contractions that require the tendon to act as a spring

Stiffer landings with reduced ground contact time tend to stress tendons more than softer landings with more bending at the hip, knee and ankle joint (3). This makes sense given that a really fast jump with less time for the muscles to help absorb force will stress the tendon to a greater degree.

Interestingly, athletes who perform better during jumping tasks tend to develop more patellar tendinopathy and pain (2). These same athletes may be better able to harness the elastic nature of tendons and jump better as a result. Unfortunately, the better you're able to produce forces in tendons, the more likely you may be to develop tendon pain.

One case study from JOSPT found that retraining jump patterns was helpful in reducing patellar tendinopathy pain (3). Some cues used in the study that may help athletes when returning to jumping after patellar tendinopathy are:

- Land "softly" to minimize landing impact

- Reduce sound during landings (also to reduce landing impact)

- Lean forward during landings (to encourage increased hip motion)

- Push hips back during landings (also to increase hip motion)

The thought here is that patients with patellar tendinopathy tend to have stiffer landings and don't adequately utilize their hips (send the hips back, bend at the hip and lean the trunk forward) during landings and instead tend to utilize the knees more (more knee flexion and less hip flexion).

Correcting these issues reduces stress on the patellar tendon, may help decrease pain and improve rehabilitation outcomes (and potentially decrease future issues). Although this is only one case study, it makes sense that modifying jump technique may be helpful in reducing pain in people with patellar tendinopathy.

The same goes for the squat and single leg strengthening exercises like lunges and step-ups. If we encourage more "hips back" and encourage more forward trunk lean we're taking some of the stress off of the patellar tendon and onto the hips and spine instead. This can be useful to modify stress through the patellar tendon throughout the rehabilitation process.

5: Dynamic valgus at the knee

As stated earlier, having dynamic valgus at the knee can increase stress through the patellar tendon. Inadequate ankle dorsiflexion can lead to this but often this is purely a technical issue that can be corrected with the right cues from a coach or feedback by standing in front of a mirror.

You'll probably want to ensure you have optimal alignment of the knee and toes during all of your chosen activities (squatting, lunging, step-ups, running, jumping, landing etc..).

So that's it for your guide to patellar tendinopathy. Hopefully you finished this read with a better understanding on the condition and how you can help folks suffering from it. Now that you've got a handle on the condition you may also want to see how the physical therapy is done. If you want a more in depth guide on how I like to get my clients out of pain and back to the weight room click HERE to check it out:

My knee cap is on fire, is that bad?

Dan Pope DPT, OCS, CSCS, CF L1

References:

- Superior results with eccentric compared to concentric quadriceps training in patients with jumper’s knee: a prospective randomised study https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1725058/pdf/v039p00847.pdf

- CURRENT CONCEPTS IN THE TREATMENT OF PATELLAR TENDINOPATHY IJSPT 2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5095939/#B83

- Rehabilitation of Patellar Tendinopathy Using Hip Extensor Strengthening and Landing-Strategy Modification: Case Report With 6-Month Follow-up JOSPT 2015 https://www.jospt.org/doi/full/10.2519/jospt.2015.6242?code=jospt-site

- Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations https://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.2015.5987?code=jospt-site

- Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:409–16.

- Neovascularisation and pain in jumper’s knee: a prospective clinical and sonographic study in elite junior volleyball players http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/39/7/423ijkey=a16cd5a3976373e3a7cb301804ef49f9f932f98a&keytype2=tf_ipsecsha

- Physio Edge 075 Tendinopathy, imaging and diagnosis with Dr Sean Docking https://www.clinicaledge.co/podcast/physio-edge-podcast/75

- Moving Beyond Exercises for Managing PFP, Patella Tendinopathy and Iliotibial Band Syndrome Sports Kongres https://youtu.be/VJIN-WT8N00

- Mechanisms and Management of Pain for Physical Therapists by Kathleen Sluka IASP Wolters Kluver

- Therapeutic Neuroscience Education - Adriaan Louw

- The association of ankle dorsiflexion and dynamic knee valgus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. 2018 Physical Therapy and Sport https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28974358

- The Relation Between Stretching Typology and Stretching Duration: The Effects on Range of Motion IJSM 2018

- The Foam Roll as a Tool to Improve Hamstring Flexibility The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Dec. 2015)

- Common Running Injuries Evaluation and Management 2018 by the American Academy of Family Physicians https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/0415/p510.html

- O'Sullivan K, McAuliffe S, Deburca N. The effects of eccentric training on lower limb flexibility: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2012; 46: 838–845

- Docking SI, Cook J. Pathological tendons maintain sufficient aligned fibrillar structure on ultrasound tissue characterization (UTC). Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016 Jun;26(6):675-83. doi: 10.1111/sms.12491. Epub 2015 Jun 9. PMID: 26059532.

- Achilles and Patellar Tendinopathy: Rehabilitation Challenges - Jill Cook - Sport Fisio Swiss 2018 https://youtu.be/h9DqAcikVLo

- Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.