Updated 7/20/21:

Key Points: This article is a monster so I’ve included the main points to getting out of low back pain and back to training below:

- Learn the basics about low back pain

- Regular activities (work too) should be resumed shortly after low back pain even if you still have pain

- Low back pain improves in the majority of people over time

- Strengthening helps reduce pain and reduces future low back pain episodes

- Temporarily modify training and lifestyle activities to allow the irritated low back to calm down

- Eliminate or modify aggravating lifestyle activities like prolonged sitting or standing

- Modify squats, deadlifts and olympic lifts to variations that cause minimal pain

- Identify and correct mobility limitations in the ankle, hip, shoulders and thoracic spine

- Mobility limitations here can increase stress on the lower back and decrease performance

- Identify the best squat stance for optimal low back performance and health

- Different squat stances place more or less stress on the lower back

- Correct technique issues in the squat, deadlift and olympic lifts

- Maintain a core braced and neutral spine position during all lifts to maximize performance and decrease low back stress

- Start gradually loading the spine through a progressive strengthening program

- Emphasizing progressively more challenging squat and deadlift variations

- Target the hip and core musculature

The article you're reading is absolutely enormous coming in at over 60 pages long! I definitely don't expect you to read this all in one sitting so I recommend putting your name and email into the box below so I can email you a downloadable PDF copy that you can read at your leisure. I'll also throw you onto the FPF newsletter so you can stay on top of the newest content coming from Fitness Pain Free!

1: Low Back Pain Basics

Low back pain is an interesting beast that will pop up from time to time when training. For some it can happen all at once when pulling a heavy deadlift off the floor. For others it happens when coming out of the hole during a heavy squat. This pain can be enough to stop us in our tracks. I know I've been one to drop the bar mid-way through a deadlift that caused some sharp pain and had me stumbling away from the barbell.

Still in others it can be a slow progression that starts as a "tightness" in the lower part of the back during lifts. This "tightness" can gradually worsen to the point where our squats and deadlift numbers are going down because the pain is so bad.

For others yet it doesn't start in the gym at all. Maybe it starts when bending over to grab something off the floor or twisting in an awkward way. Maybe you just wake up with it one day. This may feel like the worst case of all since a seemingly trivial task has crippled us and is thus keeping us from the lifts we love in the gym.

Lastly, low back pain can be a chronic condition that sticks around for months to years. Pain levels can go up and down and on those bad days performing your favorite lifts can be an absolute no go...

In most people, the large majority of low back pain has a non-specific cause. Non-specific is defined as pain that is not attributed to a known cause (1). In fact, non-specific low back pain makes up 90-95% of all back pain (1). This means that in a large majority of low back pain cases we don't know exactly why they started hurting.

Injuries in the gym however, do typically have a bit of a cause. This can generally be attributed to an overload to specific areas of the spine accompanied by a lack of spinal strength and preparation. We'll chat later about how we can use this information to our advantage to help get out of pain and hopefully stay out of pain for the long haul.

Fortunately for us, the majority of low back pain episodes will improve over time (2). Also, long gone are the days when we thought pure bed rest was the way to go to get out of pain. We now know that remaining active and getting back to your activities (including work) quickly is important and not dangerous even if you still have back pain. (2)

Here's another cool part. Low back pain is actually improved by strengthening it. (4) This is music to the ears of gym lovers. It means we don't have to give up what we love and what we love is actually helpful for getting out of pain.

Lastly, a regular strengthening program is also helpful for preventing low back pain in the future. (3, 30) That makes sense right? The human spine is actually a very strong structure (2) and can handle exercise quite well. Make the spine stronger and it will better be able to handle the stress of living life and training even better.

Now, we always need to be on the lookout for more serious issues like cancer, fractures and infections when the low back hurts. If you're experiencing any of the following issues then you need to speak to a physician immediately (2):

- History of major trauma (car accident, fall from a height, direct blow to spine)

- Associated abdominal or groin pain

- Fever

- Swelling over the spine

- Urine retention

- Fecal incontinence

- Numbness, tingling or abnormal sensations in the groin area

- Worsening weakness, numbness or tingling in the lower body

- Constant pain not affected by position or activity, worse at night

- History of cancer

- Unexplained weight loss

- No relief with bed rest

In general, if your symptoms are not improving over the course of 30 days you should always consult a physician to see if something more serious is occurring. If you're unsure whether or not your condition is more serious be sure go to the doctor as well. When in doubt, get it checked out.

So Why Does Low Back Pain Occur in the Gym?

Weight training simply places stress on the spine. Think about lifting a maximal deadlift, the spine is subject to a lot of stress during the lift. If the amount of stress we apply to the spine exceeds the spine's ability to tolerate that stress, an injury occurs. In weight training and strength sports we're often pushing the envelope in terms of loads lifted during exercises like deadlifts, squats and olympic lifts.

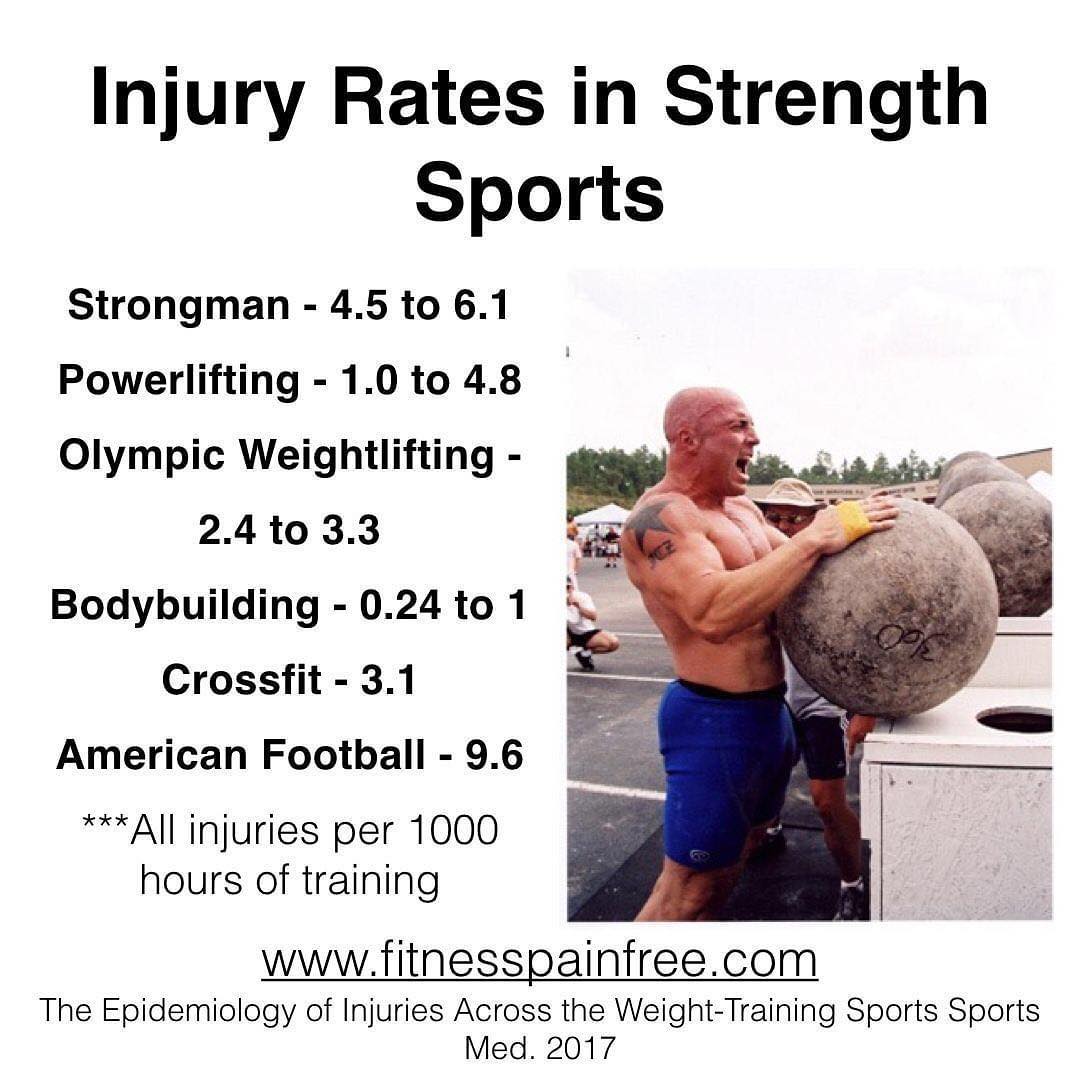

If we start looking at survey data looking at injury rates in strength sports here is what we find:

- The low back is the most commonly injured area in Strongman Athletes (5)

- The lower back is among the 3 most injured areas in Powerlifting, Olympic Weightlifting and CrossFit TM. (6, 7, 8)

This just makes sense. Lifts like the squat and deadlift simply place large amount of stress on the lower back and are thus commonly reported to create injury there (7). In lifts like the deadlift, the lower back is commonly the limiting factor for lifting more weight. If the stress of training exceeds our back's ability to handle it we may break down and become injured.

Now, weight training isn't inherently dangerous, in fact it's quite a bit safer then other forms of fitness and other sports. Check out the infographic below comparing typical strength sports to american football. However, (just like in any other physical activity) from time to time injuries will occur.

In general injuries occur when we throw more stress on the spine then it can handle. This can come in the form of sub-optimal technique, programming issues as well as poor recovery and regeneration strategies. Here are some commons reasons why I believe low back injuries occur in the gym:

- Introducing a squatting, deadlifting or olympic weightlifting program too quickly (Not being prepared for a given program and jumping straight into it) (8,9,10,11)

- Being a novice trainee (<6 months to 1 year training experience) (12,13)

- Lack of consistency with training (12,15)

- Excessive training volumes (eg: too much training via sets, reps, frequency, etc.) (8,9,10)

- Excessive training loads (using more weight then your spine can handle)

- Spikes in training volumes (eg: A sudden spike in training volume) (8,9,10)

- Lack of coaching and poor technique (11, 14)

- Poor recovery (nutrition, sleep, stress management, lack of recovery days between intense sessions) (17, 18)

- Mobility issues creating more stress on the spine (more on this later)

- Not taking prior low back injuries into account (16)

The take-away here is that low back injuries are generally multi-factorial in nature and usually can't be attributed to any one major cause. This also means that if we want to prevent future injury we'll have to address the factors that led to injury in the first place. This is an article for another day though...

How Can I Start Getting Out of Pain and Back to Training?

Now, I know I just said that strength training is helpful for getting out of pain, but if you're dealing with some serious pain then the last thing you probably want to do is load up a barbell for some heavy deadlifts. There's definitely a process to this and I'm going to help guide you through it.

I've created a 4 step plan to help you get out of pain and back to training squats, deadlifts and the olympic lifts. Here are the steps:

- Modify training and lifestyle activities to allow the irritated low back to calm down

- Identify and correct mobility limitations in the ankle, hip, shoulders and thoracic spine to reduce stress on the spine

- Correct technique issues in the squat, deadlift and olympic lifts

- Start gradually loading the spine through a progressive strengthening program

So let's begin shall we?

2: Modify training and lifestyle activities to allow the irritated low back to calm down

After a lower back injury, what's important to understand is that pain is a natural and normal protective response our brains produce (19) to make sure we don't do anything stupid and hurt ourselves further in the gym. So initially after an injury it's very important to temporarily avoid aggravating activities to give the spine time to heal and pain levels to calm down.

Modifying Lifestyle

This means 2 things:

- Your regular lifestyle activities should be temporarily modified to avoid aggravating your low back

- Your regular gym training should be temporarily modified to avoid aggravating your low back

After a low back injury there are predictably things that feel pretty good and things that feel pretty bad. In some folks when they have low back pain rounding the back feels really bad. I find this is in athletes who have hurt their spine in a rounded (flexed) position like in the bottom of a squat or deadlift.

For this reason things that require low back rounding tend to feel bad:

- Sitting (especially for prolonged periods)

- Driving (due to extended periods of sitting)

- Bending over to pick things off the floor

- Putting socks on

For these folks it's a good idea to temporarily avoid this position so we don't aggravate things further. So what can you do if you're one of these folks?

- Work at a standing desk instead of sitting

- Sit in a tall seat (reduces low back rounding)

- Break up bouts of sitting with frequent walks and periods of standing

- Sit with a roll behind the lower back to keep the spine extended more while sitting

- Sit in a more extended (arched) position of the spine when sitting

Now, in other people their spines won't like to do the opposite motion (arching or extending the spine). This pain pops up in folks with exercises that force the lower back into more extension. This can classically happen during overhead press and jerks because the low back is exposed to a lot of extension. For this reason things that require the low back to extend (arch) tend to feel bad. For example:

- Reaching overhead or working overhead

- Standing for prolonged periods

- Lying on your stomach

For these folks it's a good idea to temporarily avoid this position so we don't aggravate things further. So what can you do if you're one of these folks?

- Sit more frequently throughout the course of the day

- Sit with the lower back rounded (flexed)

- Break up bouts of standing with frequent periods of sitting

- Stand with the pelvis in a posterior pelvic tilt (tuck your tail liked a scared dog)

- Stand with 1 leg elevated on a stool to round the back some

Not only will this make your day a lot more pleasant but it may actually speed up your rehab process because you're not frequently irritating the injured area.

It's also important to understand that everyone will have a specific "flavor" of low back pain. Some are very cut and dry and will follow one of the two patterns above. Others will hurt in both directions. Some hurt all of the time and don't follow either pattern.

Initially it will be important to be mindful of which activities create pain so we can modify them and allow the pain to die down. Over the course of time we'll re-introduce those movements gradually as pain improves.

My general rule of thumb is "to be nice to your lower back." Basically I mean do a lot of activity that feels good to the low back and temporarily modify and or leave out the activities that feel bad. Like I said earlier, exercise (and motion in general) is good for the painful lower back. We want to be as active as possible without irritating the lower back along the way.

The second part of the solution will require making some major modifications to any exercises that are aggravating in the gym.

We're going to want to temporarily unload the joint by avoiding aggravating movements for somewhere between 4-6 weeks following an injury to the lower back

I know this is tough to hear for someone who absolutely loves to lift, but it's important for long term success during rehabilitating and if we skip this step we could be setting ourselves up for long term failure and frequent future exacerbations. Also keep in mind that if a given movements feels great, then there's no need to modify. We only need to modify the movements that are painful.

Common culprits that may need to be modified initially:

- Squatting

- Olympic lifts (cleans, snatches, jerks)

- Deadlifts

- Overhead press

My general rule of thumb for modifying exercise is that any movement that creates more than a 3/10 pain (on a 0-10 pain scale) during, that night or the day following training needs to be modified. Obviously this is going to be different from person to person and it will take some experimentation to get right. I'll show you exactly how to do this for every common movement above. We'll also cover pain in depth and what's ok to push into and what's not later in the article.

How long you'll have to modify also depends a lot on the individual. Some take longer, some shorter. I've had bouts of lower back pain that had me modifying for over 6 months. I've worked with people where that process is a year or longer. Some only take a few days or weeks.

Stay patient and do your best not to get frustrated along the way. Remember, low back pain is super common and you've got plenty of people fighting the same fight as you and plenty more who have come through in a better place after.

To help you navigate through the modification process I've created principles for modifying the squat, olympic lifts and deadlift to help you stay within the pain parameters discussed above when training.

You'll learn some simple principles that allow us to increase or decrease stress on the spine (decrease stress for now). With these principles we can adjust exercise technique to decrease stress on the spine and if these modifications aren't enough to decrease pain within our pain guidelines (< or = 3/10) then I've supplied a series of exercises to try until we find a movement we can load.

Deadlifting and Lower Back Pain Principles:

Generally speaking, 3 things that increase stress to the lower back when deadlifting are:

- Going too far outside of “Neutral Spine” - The muscles around the spine fire best and the stresses on the spine are minimized when the spine is kept in a neutral position while squatting.

- Deeper deadlifts (rack pull vs. deadlift from floor) are more stressful because they require more lower back rounding then more shallow deadlifts

- Mobility issues at the hamstrings can create more lower back rounding

- Stance effects this as well, for some neutral spine will be much easier to maintain with a sumo stance.

- Greater loads - The more weight on the bar generally equates to more stress on the spine

- Faster lifting speeds also increase stress on the spine

- More forward torso inclination - Inclining the torso forward and sending the hips back further during a deadlifts increases stress to the spine. Think of the difference between a romanian deadlift and a trap bar deadlift.

6 Pro Tips For Reducing Lower Back Pain During Deadlifts

Learn how to maintain a neutral spine and brace appropriately during deadlifts

- Decrease depth of deadlifts to reduce lower back rounding at the bottom of the squat

- Exercise examples: Rack pulls, partial range dumbbell deadlifts, elevated handle trap bar deadlift

- Decrease depth of deadlifts to reduce lower back rounding at the bottom of the squat

Mobilize the hamstrings - If hamstring mobility is an issue then mobilize hamstrings prior to lifting

Decrease the load lifted or speed of lifting - Taking weight off the bar will help to decrease stress on the spine as well as slowing down the speed of lifting.

- Try tempo lifts with an emphasis on a slower lower

- Add 2-3 repetitions to your working sets to encourage less weight on the bar but to still get a training effect

- Utilize a deadlift variation that forces you to use less load like a dumbbell romanian deadlift

Use a deadlift variation that makes you more upright - A more upright deadlift variation decreases stress on the spine.

- Sumo and trap bar deadlifts over conventional deadlifts

Try hip thrusts - Hip thrusts work the lower back, hip and hamstring muscles similarly to a deadlift but have less compressive force through the spine and are generally well tolerated for painful lower backs.

Substitute leg strength work - If all else fails and all movements are painful then try utilizing single leg exercises. These still allow some leg strength training while decreasing stress on the spine

- Single leg deadlifts, kick stand romanian deadlifts and good mornings

Deadlift Modification Ladder for Lower Back Pain - When you are unable to eliminate pain by slowing down reps, attempting a higher rep range or modifying technique, use the ladder below to find a pain free deadlifting variation.

Squatting and Lower Back Pain Principles:

Generally speaking, 3 things that increase stress to the lower back when squatting are:

- Going too far outside of “Neutral Spine” - The muscles around the spine fire best and the stresses on the spine are minimized when the spine is kept in a neutral position while squatting.

- Deeper squats are more stressful because they require more lower back rounding then more shallow squats

- Mobility issues at the hips and ankles can create more lower back rounding

- Squat stance effects this as well, for some neutral spine will be much easier to maintain with a bit wider stance or more toe out.

- Greater loads - The more weight on the bar generally equates to more stress on the spine

- Faster lifting speeds also increase stress on the spine

- More forward torso inclination - Inclining the torso forward and sending the hips back further during a squats increases stress to the spine. Think of the difference between a barbell box squat and an upright front squat

6 Pro Tips For Reducing Lower Back Pain During Squats

Learn how to maintain a neutral spine and brace appropriately during squatting

- Decrease depth of squatting to reduce lower back rounding at the bottom of the squat

Decrease the load lifted or speed of lifting - Taking weight off the bar will help to decrease stress on the spine as well as slowing down the speed of lifting.

- Try tempo lifts or add a pause to the bottom position of the squat

- Add 2-3 repetitions to your working sets to encourage less weight on the bar but to still get a training effect

- Utilize a squat variation that forces you to use less load like a front squat or goblet squat

Stay more upright during squats or use a variation that makes you more upright - A more upright squat variation decreases stress on the spine.

- Front squats over back squats

- High bar back squats over low bar back squats

- Goblet squats and double kettlebell front rack squats - Very upright with minimal spinal stress and still challenging

Correct mobility limitations in the hips and ankles

- Mobilize both hips and ankles prior to squatting

- Utilize a heel lift or olympic lifting shoes

- Ensure you utilize your full mobility to stay neutral while squatting after mobilizing

Try hip thrusts - Hip thrusts work the lower back, hip and hamstring muscles similarly to a squat but have less compressive force through the spine and are generally well tolerated for painful lower backs.

Substitute leg strength work - If all else fails and all movements are painful then try utilizing single leg exercises. These still allow some leg strength training while decreasing stress on the spine

- Split squat, lunge, step-up and hip thrust variations

Squat Modification Ladder for Lower Back Pain - When you are unable to eliminate pain by slowing down reps, attempting a higher rep range or modifying technique, use the ladder below to find a pain free squatting variation.

Overhead Press and Lower Back Pain Principles:

With lower back pain the overhead press may need to be modified. Several factors influence stress on the lower back during overhead press:

- Total Load - Increased weight on the bar will increase demand on the spine

- Postural Demands - Different press variations are more or less challenging to maintain a neutral position of the spine, ribcage and pelvis. For example, a barbell press is most challenging to stay neutral, followed by a dumbbell overhead press and finally a seated dumbbell overhead press.

- Technique - Excessive rib flair, lumbar extension (arching) or anterior pelvic tilt all decrease our ability to brace appropriately and can increase stress on the spine. This can be caused by poor technique, limited mobility or weakness.

- Mobility Restrictions - Limited thoracic spine or shoulder mobility may cause increased rib flair and lumbar extension during the overhead press

Weakness - A lack of strict overhead pressing strength may cause athletes to extend in the lower back to take advantage of the stronger pec muscles and put the shoulders in a stronger position to produce force during overhead pressing.

5 Tips For Reducing Lower Back Stress in the Overhead Press

Reduce Load on the Bar

- Take some weight off the barbell

- Consider using tempos and paused reps to get a training effective while lowering weight on the bar

Choose Easier Exercises Based on Postural Demands

- Barbell overhead press > Dumbbell Overhead Press > Seated Dumbbell Overhead Press

- Barbells must travel around the face increasing extension of the lower back (and subsequent core stability to maintain neutral)

- Dumbbells don’t have to travel around the face and thus reduce stress on the core

- ½ kneeling and sitting down posteriorly tilts the pelvis and makes staying out of extension in the lower back easier

- Barbell overhead press > Dumbbell Overhead Press > Seated Dumbbell Overhead Press

Fix Exercise Technique

- Utilize cues and mirror or video feedback to ensure athletes press with a neutral spine position, avoiding excessive anterior pelvic tilt and rib flair

Correct Mobility Limitations

- Correct underlying mobility limitations in the shoulders and thoracic spine

- Consider modifying pressing exercise if severe overhead mobility limitations persist

- Eg: Incline dumbbell press, landmine press

Address Weakness - If excessive lower back extension (arching) is present due to excessive load on the bar, decrease the weight to improve exercise technique.

Overhead Press and Lower Back Pain Modifications: When you are unable to eliminate symptoms by improving technique or reducing load on the bar use these modifications to find the right movement for your athlete.

Olympic Weightlifting and Lower Back Pain Principles:

Generally speaking, 3 things that increase stress to the lower back when olympic weightlifting are:

- Going too far outside of “Neutral Spine” - The muscles around the spine fire best and the stresses on the spine are minimized when the spine is kept in a neutral position while lifting. We’ll break the olympic lifts down into 2 parts:

- The Pull:

- Pulling from the floor is more stressful than pulling from a hang or elevated surface (blocks) because it requires more lower back rounding

- Mobility issues at the hamstrings can create more lower back rounding

- The Catch and Squat:

- Deeper squats are more stressful because they require more lower back rounding then more shallow squats. Think of the difference between catching a clean in a full squat vs. a ½ squat

- Mobility issues at the hips and ankles can create more lower back rounding

- Squat stance effects this as well, for some neutral spine will be much easier to maintain with a bit wider stance or more toe out.

- The Pull:

- Greater loads - The more weight on the bar generally equates to more stress on the spine

- More forward torso inclination - Inclining the torso forward and sending the hips back while coming up out of the hole in a clean or snatch increases stress to the spine.

4 Pro Tips For Reducing Lower Back Pain During Olympic Lifts

Limit lumbar flexion (rounding) by improving technique and modifying squat and pull depth - Ensure you keep a braced neutral spinal position throughout the lift or try these strategies below

- The starting depth for the pull:

- Utilize hang variations and pulling from blocks over pulling from the floor

- The catch and squat:

- Limit the depth of the squat or utilize power variations over full squat variations

- The starting depth for the pull:

Decrease the load lifted - Taking weight off the bar will help to decrease stress on the spine

- Utilize hang variations and pauses (at knee or mid-thigh etc.) within reps to decrease load on the bar but still work technique and get a training effect

- Add 2-3 repetitions to your working sets to encourage less weight on the bar but to still get a training effect

Stay more upright when coming out of the hole in a clean or snatch - A more upright squat variation decreases stress on the spine.

- This may require you to reduce the load on the bar

Correct mobility limitations in the hamstrings, hips and ankles

- Mobilize both hips, hamstrings and ankles prior to squatting

- Utilize a heel lift or olympic lifting shoes

- Ensure you utilize your full mobility to stay neutral while squatting after mobilizing

Olympic Weightlifting Modification Ladder for Lower Back Pain - When you are unable to eliminate pain by cleaning up your exercise technique, use the ladder below to find a pain free olympic weightlifting variation.

Jerk and Lower Back Pain Principles:

With low back pain the jerk may need to be modified for safety and to meet the athlete where they are in terms of strength and fitness. Several factors influence how challenging the jerk is for these athletes:

- Total Load - Increased weight on the bar will increase demand on the lower back

- Postural Demands - Different jerk and press variations are more or less challenging to maintain a neutral position of the spine, ribcage and pelvis. For example, a barbell split jerk is more challenging to maintain neutral then a push jerk.

- Technique - Excessive rib flair, lumbar extension (arching) or anterior pelvic tilt all decrease our ability to brace appropriately and can increase stress on the spine. This can be caused by poor technique, limited mobility or weakness.

- Mobility Restrictions - Limited thoracic spine and shoulder mobility may cause increased rib flair and lumbar extension during the jerk

Weakness - A lack of strength in the lockout portion of the jerk may cause athletes to extend in the lower back to take advantage of the stronger pec muscles and put the shoulders in a stronger position to stabilize the weight overhead.

5 Tips For Reducing Lower Back Pain in the Jerk

Reduce Load on the Bar

- Take some weight off the barbell

Choose Easier Exercises Based on Postural Demands

- Barbell Split Jerk > Barbell Push Jerk

- The trail leg of the split jerk makes it more challenging to keep a neutral position of the spine then in comparison to a push jerk

- Barbell Split Jerk > Barbell Push Jerk

Fix Exercise Technique

- Utilize cues and mirror or video feedback to ensure athletes jerk with a neutral spine position, avoiding excessive anterior pelvic tilt and rib flair

- This goes for the dip and drive portion of the jerk as well as the catch overhead

- Utilize cues and mirror or video feedback to ensure athletes jerk with a neutral spine position, avoiding excessive anterior pelvic tilt and rib flair

Correct Mobility Limitations

Correct underlying mobility limitations in the shoulders and thoracic spine- Keep in mind you’ll need good trail leg hip extension mobility in order to stay in neutral spine during split jerks

- Consider Modifying Jerks to other press modifications if severe overhead mobility limitations persist

- Eg: Incline dumbbell press, landmine press

Address Weakness - If excessive lower back extension (arching) is present due to excessive load on the bar, decrease the weight to improve exercise technique.

Modify to Traditional Overhead Press - If athletes can not perform either jerk variation without symptoms, then utilize the overhead press modifications instead.

Jerk and Lower Back Pain Modifications

When you are unable to eliminate symptoms by improving technique or reducing load on the bar use these modifications to find the right movement for your athlete.

So now you should be armed with the knowledge required to modify your training to unload the hip. Just keep in mind that after an injury often times the area won't tolerate the loads and volume that it normally does. For this reason you may also have to reduce not just the weight but also the sets, reps and or frequency (how many times you perform the lift per week) on some of your lower back intensive lifts. Onto the next step...

3: Identify and correct mobility limitations in the ankle, hip, shoulders and thoracic spine to reduce stress on the lower back

In order to perform olympic lifts, deadlifts and squats we need adequate mobility. An important concept to understand is that if you're lacking mobility at one joint then you'll be forced to make up that mobility at another joint. If we're lacking mobility at any of these areas, we'll end up making up for some of this at the lower back. This increases stress to the lower back and can perpetuate injury.

Here's a specific example. If we're limited with ankle flexibility then it will force the torso to incline forward when we squat (more explanation on this later in the article). More torso inclination generally equates to more stress on the spine. Basically if we can't bend well from the ankles then we force more stress on the lower back. Check out the video below to see what I'm talking about:

Here are the areas we need to assess and then correct to ensure the low back isn't working overtime:

- The thoracic spine

- The hip

- The ankle

- The front rack (for the clean)

- The shoulder (for the snatch and overhead squat)

Assessing Mobility in the Thoracic Spine and Shoulders

Check out the video below to see my favorite assessment for the thoracic spine and overhead mobility:

If you find that you've got a restriction in the thoracic spine then gaining some mobility here can help reduce some of the stress in your hips during squats. Here are a few of my favorite thoracic spine mobility exercises below:

If you find you've got an overhead mobility limitation here are some of my resources to help you correct this:

Assessing Mobility in the Hip

Lacking hip flexion mobility will force compensation (flexion or rounding) at the lower back. Check out the video below for an explanation and how I assess for hip mobility issues in the squat:

If you find you have a mobility restriction in the hip here are some of my favorite mobility drills to help improve that problem:

Another area of the hip that's critical for optimal technique and lower back health are the hamstrings. If we're stiff in the hamstrings (and neural structures) that reside in the back of the leg we won't have an optimal bar path during deadlifts and olympic lifts.

This can also show up as compensation in the lower back (flexion or rounding) at the start of these lifts:

So we'll want to ensure that we have enough hamstring mobility to deadlift efficiently in the future. Here's my favorite assessment for the hamstrings below:

Once you've determined whether or not you have a mobility restriction, it's time to mobilize the area. Check out the video below to see some of my favorite mobilizations along with another assessment and explanation of why hamstring mobility is important for deadlifts and olympic weightlifting:

Lastly, the front side of the hip is going to need some love and attention as well. If the front of the hip (aka the hip flexors) are stiff this can lend to increased motion (extension) of the lower back during split jerks.

This can also occur during the clean and snatch during triple extension:

Lucky for us, the assessment is fairly simple. Check out the thomas test below:

If you find you've got some restriction in the hip flexors you'll want some mobility exercises to improve hip extension motion followed up by some motor control or technique drills to ensure you carry that new mobility into your olympic lifts. Check out the video below for mobilization and technique reinforcement exercises:

Assessing Mobility in the Ankle Joint

Ankle mobility is important for reducing stress in the lower back but also for achieving enough depth in the squat and maintaining an upright torso in the bottom of the squat. Check out the video below to learn how to assess your ankle mobility:

If you find a restriction, it's a good idea to work on correcting this. Check out the video below to see some of my favorite ankle mobility exercises:

Assessing Mobility in the Front Rack

If there is a restriction in front rack mobility it will lead to compensation and increased motion at the lower back. Fortunately for you I've created an in depth article to help you figure out if you have any mobility restrictions in your front rack and how to improve it:

The Ultimate Front Rack Mobility Guide

These mobility drills can be started immediately after starting rehabilitation and should be continued throughout. Once we have adequate motion in all joints involved we'll also have to ensure that we have adequate technique.

Keep in mind that you may have spent years developing a specific exercise technique. If this was with poor technique then this will be a tough habit to break. Just because we have the mobility to get into a specific position doesn't necessarily mean we'll use that technique (especially if we don't have the strength in that position as well).

Let's use ankle mobility as an example. Just because we now have the motion doesn't mean that we'll use it. After mobilizing the ankles we may need a few cues to now use this new motion. Check out the video below to see what I'm talking about:

In this case a few cues were needed to get into a position that reduces stress on the lower back. We'll be discussing technique in more depth later on in the article series...

4: Identify the proper squat stance for your unique hip anatomy

One of the reasons I'm so adamant about choosing the right squat stance for your hips is because squat stance will dictate the amount of lower back motion during the squat. As we spoke earlier, more motion at the spine can equate to more stress and we're looking for an optimal dosage in the spine to promote optimal performance and health both.

As we descend towards the bottom of the squat we'll naturally start running out of range of motion at the ankles, knees and hips. Once we hit the end of our mobility at these joints the lower back will naturally start to move more to ensure full motion in the bottom of the squat.

This lumbar flexion or lower back rounding at the bottom of the squat is commonly known as "butt wink". Check out the video below to see what I'm talking about.

The reason why squat stance is important is because it will influence the amount of mobility we can access at the hip in the bottom of the squat. If we choose a squat stance that maximizes range of motion at the hip a few things will occur:

- We'll be forced to COMPENSATE LESS at the lower back in the bottom of a squat

- We'll be able to GET DEEPER into the squat

- We'll be able to remain MORE UPRIGHT in the bottom of the squat (great for the snatch and clean)

These are all favorable for improving our squatting and olympic weightlifting.

Keep in mind that squat stance will vary widely based not only on your hip anatomy but also based on your goals. Olympic weightlifters looking for maximum depth in the squat and a nice upright torso for carry over to cleans and snatches may utilize a more narrow stance with less toe out. Powerlifters looking to just break parallel and lift as much weight as possible may adopt a wider stance to maximize their potential to lift weight.

So how do we determine the most optimal stance for your squat? Check out my assessment below for the hip to figure out your optimal squat stance:

Once you've identified your best squat stance we'll want to start utilizing this stance once we return back to squatting. After you've gone through a period of unloading the squat and other painful movements it's time to start slowly introducing them back in again. However, we need to make sure that technique is dialed in on these movements before we jump right back in...

5: Correct technique issues in the squat, deadlift and olympic lifts

The position we're looking to keep when performing our favorite movements in the gym is going to be called a "braced neutral" position. Braced refers to flexing the abdominal or "core" muscles to prepare the spine for handling heavy loads while lifting. Neutral refers to finding a position mid way between maximal rounding and arching.

The idea behind a neutral spinal position is that it evenly dissipates forces throughout the spine when lifting. If we lift with a lot of rounding or flexion of the spine this places more stress on the structures on the anterior or front part of the spine (In most studies this is the spinal disc) (21). It also reduces the low back muscle's efficiency to reduce shearing forces in the spine (21). If we lift in a lot of extension or arching we place more compressive stress on the elements on the posterior or back side of the spine (21).

Ideally if we can stay neutral during our lifts we're evenly distributing forces throughout the entirety of the spine and not placing more stress on either portion. Also, most lifters at the elite level attempt to maintain a neutral spinal position in their lumbar spine for maximal efficiency during the lift. (Obviously variation exists from lifter to lifter and sport to sport, this is a generalization)

Lastly, as described earlier, it is impossible to prevent movement in the spine during squats and deadlifts. The deeper we go into a squat and deadlift, the more flexion (rounding) the lower back will encounter. Although this may increase stress to the lower back it certainly is not a reason not to use full range of motion with these exercises. It is however a potential reason why folks with low back pain have a tougher time with deep squats and full range deadlifts and do better with partial ranges.

Side Note: The research is far from cut and dry when determining if "neutral spine" is safer when lifting for the prevention of low back pain. From the evidence we have thus far, lifting with a flexed (rounded) lumbar spine DOES NOT predict future low back pain in occupational settings (22). In fact folks with low back pain tend to lift with a stiffer "more neutral" spine then folks without low back pain (23). This makes sense given that people with painful lower backs probably don't want to move more through the painful area and instead tend to compensate by moving from other areas. (Just keep in mind that this is my own hypothesis though and not conclusive evidence)

The two most important movements to learn this braced neutral position is in the squat and deadlift. If you can find braced neutral for these movements you can find this position for the clean and snatch as well.

Check out my two videos below to see how you can maintain a neutral position for both the squat and deadlift:

The other important technical variable in both the squat and deadlift is going to be torso inclination. Basically the more inclined the torso is forward, the more stress will fall on the lower back (21). This is because as we incline our torso forward it becomes more challenging for the spinal segments to resist what are called shear forces.

So basically having more forward torso inclination will increase the stress on the lower back. (21) Also keep in mind that more torso inclination isn't bad. Often times it's actually the strongest position for a given athlete. However, more torso inclination will equate to more stress on the lower back. This is one situation where optimal performance and optimal health don't always align.

Also keep in mind that if we alter torso angle we're also shifting the stress elsewhere. Less torso inclination will also drive more knee bending and shift the stress down a few joints. Check out the image below to see what I'm talking about:

If you're chronically injuring your lower back and have a ton of forward torso inclination, it may be a good idea to try and get more upright for less pain in both the short of long term.

Another movement which can lead to some issues in the lower back and contribute to injury is the jerk (and overhead pressing in general). One common compensation with the jerk and during overhead pressing is excessive lumbar spine extension. Check out the images below to see what I'm talking about:

Remember that limited mobility in the shoulder and thoracic spine (and trail leg hip flexor in the split jerk) can lead to over extension in the lower back so be sure to assess this area and mobilize all areas that need it. Also keep in mind that some folks will overextend the lower back during overhead press due to a lack of strength in the shoulders to press with a neutral spine position. This may mean that you need to lower the weights some to improve your technique.

Lastly, I've made an infographic below to help correct common over extension problems in the lower back during overhead press and jerks:

6: Start gradually loading the spine through a progressive strengthening program

Exercise helps us rehabilitate from an injury through a process called mechanotransduction (24). Basically exercise causes a cascade of reactions that leads to our tissues healing and adapting to the stress that we're throwing at it (24). In other words, you need to show your body (our low back in this case) the same stresses it needs to be able to handle so that it can adapt and heal.

With this in mind, exercise dosage becomes incredibly important. When you have a headache taking 2 aspirin can get the job done and have you feeling better. If you decide to take the entire bottle then you'll most likely end up dead. The aspirin wasn't the problem, it was the DOSAGE of the medicine. Think of exercise as the medicine that will heal your low back. We just need to be very careful with our dosage of exercise medicine.

What needs to be kept in mind is that exercise dosage actually needs to start pretty low and then will need to ramp up over the course of time as the lower back improves.

Remember that pain is your body's way of trying to keep you safe. Your body is smart. It remembers the past stresses you've thrown at your low back that created issues in the first place. It isn't going to allow you to bounce straight back into training for fear of repeating past mistakes. You've violated your body's trust and it's going to take some time and diligence to win back trust and get pain to go down and get you back to hitting squat and deadlift PRs.

So, how do we dose exercise, build back our body's trust and get back to training? Check out the images below to see two styles of training that lead to a lack of results:

In this example we see that not enough training stress may not get the effect we want and too much stress and we go backwards. It's kind of a goldilocks situation. Too much stress and we violate the body's alarm system and get more pain. Not enough stress and we may not make a change. Remember that exercise will help heal our tissues and if we don't apply the medicine we may not get the improvement we want.

I like to use pain as a guideline for loading the low back. Basically if we're keeping pain below a certain threshold then we're probably doing things appropriately. Having small amounts of pain is not only normal but can be a sign that we're applying the right amount of stress to the joint (19).

As you progress over the course of time we just dial up the stress to match where the low back is in terms of rehabilitation. What this also means is that as our low back improves we can slowly start leaking exercises back into our training program that were previously too painful. As discussed previously I like to use pain as a guide for exercise dosing in rehabilitation programs. Here are my guidelines to help determine dosage of exercise during rehabilitation using pain as a guide:

- Pain should be minimal or at or below a 3/10 on a 0-10 pain scale during exercise

- Pain levels should return to baseline following exercise and the following day

- Pain and function should be improving on a weekly and monthly basis

- Exercises should be introduced with low volume and intensity initially (low loads, sets, reps, days / week)

The other important thing to keep in mind is that progress can be made in ways other then improvements in pain (1). If we're having improvement in function and pain levels are staying at similar levels, that's also progress (1). For example, let's look at an athete's training journal while recovering from low back pain:

- Week 1: 5 x 5 Deadlifts @225lbs - Pain level 3/10

- Week 1: 5 x 5 Deadlifts @245lbs - Pain level 3/10

- Week 1: 5 x 5 Deadlifts @265lbs - Pain level 3/10

- Week 1: 5 x 5 Deadlifts @285lbs - Pain level 3/10

In this case pain levels stay at a 3/10 over the 4 weeks of training. For some this would feel like no progress. However, the weights go up by 20lbs every week. This is great progress and I bet at week 4 in this example our athlete could probably deadlift 225lbs with less pain then on week 1. So if pain levels are staying similar but we're seeing improvements in:

- Weights lifted in the gym

- Difficulty of exercise variation (i.e. Back squat over goblet squat)

- Exercise volume (total sets, reps, frequency of training)

then you're moving in the right direction...

Fortunately for us, the large majority of research on low back pain favors an active approach to rehabilitation (1, 4, 25). Several studies have even shown that squats and deadlifts are beneficial for reducing pain (4, 26) . We actually have some research to show that loaded deadlifts improve low back pain just as well as basic motor control drills (27):

The other cool aspect of training loaded movements like deadlifts for low back pain is that not only are they beneficial for getting out of pain but they're also great for building up weakened and atrophied (loss of muscle size) muscles in the spine following an injury (27). (again as well as motor control drills)

This is great news for us because the movements we want to get back to are the same movements that will help us get out of pain.

However, we do have to pump the brakes a bit when starting off though. Remember our pain guidelines from above. We actually have some research to show that patients who have high levels of pain, disability and poor low back endurance tend not to do as well with deadlifts for rehab (29). Check out the infographic below to see what I'm talking about:

So what this does mean is that in the initial stages of rehabilitation when pain levels are high we can start training the spine with lower level exercises. Over the course of time when things start improving we can slowly progress back to previously painful movements like squats, deadlifts and olympic lifts.

So, now that you've got the educational component down, you've been modifying your lifestyle and exercises in the gym, now we need to get to the strengthening part. Strengthening should be progressive in nature and it also needs to train the specific muscles that are used in your typical training program. This means a lot of hip and core work. Here are some of my favorite core and hip strengthening exercises I like to use commonly:

For the Glute Medius and Lateral Core Muscles:

For the Anterior Core and Hip Flexors:

Plank and deadbug variations also fall into this category as well and are also good variants.

For the Glute Max and Posterior Hip Muscles

Also keep in mind that all lunge, step-up and single leg squat and deadlift variations fit into this category. I generally start athletes with a single leg strength variation that keeps the torso more upright (lunge / step-up) and then progress towards more torso inclination (single leg deadlift) over time to increase stress on the spine as pain improves.

The evidence we have on low back rehabilitation programs (specifically those that use heavy loading as a treatment) shows a duration of rehab around 8 weeks to make progress (27, 28, 29). Just keep in mind that depending on the severity of the injury, how long you've been in pain and how intense of a program you want to get back into, this could be shorter or longer. Also, these studies are looking at IMPROVEMENTS in low back pain and function, they are not saying that an exercise program will completely eliminate symptoms. For many people an absolute elimination in pain is not a reasonable goal.

I've seen athletes get back in as soon as 1-2 weeks and other take up to a year or more. The name of the game is patience and don't assume that you should be making faster progress because someone else you know did.

Also keep in mind that your exercise program needs to slowly progress back to squatting, deadlifting and olympic lifts (if those are the lifts you want to get back to) over time. That means slowly introducing these movements as the low back tolerates them. Keep in mind the modification ladders discussed earlier in the article. One easy strategy for returning to these lifts is to start with the easiest variations on the ladder and progress up the ladder every 2-4 weeks as the low back tolerates each movement.

So now that we went over these principles to help get you out of pain, how does the program end up looking? Let's put it all together.

Return to Weight Training After Low Back Pain Program

So here's an outline of a typical program to get you out of pain and back to training:

Week 0-4: Train 3 days / week

- Eliminate aggravating exercises (full depth squats, deadlifts, full depth olympic lifts)

- Modify squats, deadlifts and olympic lifts to continue training while allowing the low back pain to calm down (Use modification ladders to find appropriate modifications)

- Hang power olympic lifts

- High handle trap bar deadlifts with tempo

- Partial range front squat to box

- Begin core and hip strengthening program - 3x per week

- Begin mobility program to address limitations - 5x per week

- Progress to the next phase when mostly pain free with daily activities (~2-4 weeks)

Week 4-8: Train 3 days / week

- Advance squat, deadlifts and olympic lift challenge for the low back

- Power olympic lifts from floor

- Low handle trap bar (no tempo)

- Goblet squat full range (pause in bottom)

- Advance core and hip strengthening program - 3x per week

- Continue Mobility Program - 5x per week

- Progress to the next phase when ready to tolerate more challenging squat, deadlift and olympic lifting variations (~2-4 weeks)

Week 8-12: Train 3 days / week

- Advance squat, deadlifts and olympic lift challenge for the low back

- Full depth olympic lifts (slow descent into bottom of squat with pause in bottom)

- Conventional deadlift from floor (3 second lower to the floor)

- Front squat full range

- Advance core and hip strengthening program - 3x per week

- Continue Mobility Program - 5x per week

Week 12+: Train 3 days / week

- Continue building back to your normal training program

So that's it! What a long article huh? Who would have thought there was so much to write about with the low back huh? Anyway, I hope this article was helpful in showing you how to get out of pain and back to training your favorite lifts.

If you want a little more guidance on how to get out of low back pain I have a completely done for you training program to help you get out of pain and back to training. It's called "Ultimate Low Back" and it will be out soon!

I've taken the guesswork out of finding the right amount of sets and reps and which exercises to use and which to avoid. It's all 100% outlined. Consider it your roadmap to get out of pain and back to training.

The Ultimate Training Program to Get Out of Lower Back Pain

Low back pain assassin,

Dan Pope DPT, OCS, CSCS, CF L1

References:

- Oliveira, C. B., Maher, C. G., Pinto, R. Z., Traeger, A. C., Lin, C.-W. C., Chenot, J.-F., … Koes, B. W. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. European Spine Journal.

- Delitto, A., George, S. Z., Van Dillen, L., Whitman, J. M., Sowa, G., Shekelle, P., … Godges, J. J. (2012). Low Back Pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 42(4), A1–A57.

- Shiri, R., Coggon, D., & Falah-Hassani, K. (2017). Exercise for the Prevention of Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(5), 1093–1101.

- Welch, N., Moran, K., Antony, J., Richter, C., Marshall, B., Coyle, J., … Franklyn-Miller, A. (2015). The effects of a free-weight-based resistance training intervention on pain, squat biomechanics and MRI-defined lumbar fat infiltration and functional cross-sectional area in those with chronic low back. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 1(1), e000050–e000050. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000050

- Winwood, P. W., Hume, P. A., Cronin, J. B., & Keogh, J. W. L. (2014). Retrospective Injury Epidemiology of Strongman Athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(1), 28–42.

- Strömbäck, E., Aasa, U., Gilenstam, K., & Berglund, L. (2018). Prevalence and Consequences of Injuries in Powerlifting: A Cross-sectional Study. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 6(5), 232596711877101.

- Keogh, J. W. L., & Winwood, P. W. (2016). The Epidemiology of Injuries Across the Weight-Training Sports. Sports Medicine, 47(3), 479–501. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0575-0

- The Development and Application of an Injury Prediction Model for Noncontact, Soft-Tissue Injuries in Elite Collision Sport Athletes. (n.d.). Retrieved August 01, 2016, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46288877_The_Development_and_Application_of_an_Injury_Prediction_Model_for_Noncontact_Soft-Tissue_Injuries_in_Elite_Collision_Sport_Athletes

- Relationship Between Training Load and Injury in Professional Rugby League https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tim_Gabbett/publication/49775412_Relationship_between_training_load_and_injury_in_professional_rugby_league_players/links/551894590cf2d70ee27b41ad.pdf

- Training and game loads and injury risk in elite Australian footballers. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Brent_Rogalski/publication/234699103_Training_and_game_loads_and_injury_risk_in_elite_Australian_footballers/links/53dadd6b0cf2a19eee8b3f9f.pdf

- The risk of injuries among CrossFit athletes: an Italian observational retrospective survey. Tafuri S1, Salatino G2, Napoletano P3, Monno A4, Notarnicola A

- A 4-Year Analysis of the Incidence of Injuries Among CrossFit-Trained Participants Orthop J Sports Med. 2018 Oct; 6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6201188/

- Injury Incidence and Patterns Among Dutch CrossFit Athletes Orthop J Sports Med. 2017 Dec; 5(12): 2325967117745263. Published online 2017 Dec 18. doi: 10.1177/2325967117745263 Mirwais Mehrab, BSc,*† Robert-Jan de Vos, MD, PhD,‡ Gerald A. Kraan, MD, PhD,† and Nina M.C. Mathijssen, PhD†

- Injury Rate and Patterns Among CrossFit Athletes Orthop J Sports Med. 2014 Apr; 2(4): 2325967114531177. Benjamin M. Weisenthal, BA,* Christopher A. Beck, MA, PhD,† Michael D. Maloney, MD,‡ Kenneth E. DeHaven, MD,‡ and Brian D. Giordano, MD‡§

- Musculoskeletal injuries in Portuguese CrossFit practitioners. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2019 Feb 5. [Epub ahead of print] Minghelli B1, Vicente P2.

- INJURY RISK IS ALTERED BY PREVIOUS INJURY: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE AND PRESENTATION OF CAUSATIVE NEUROMUSCULAR FACTORS Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Oct; 9(5): 583–595. Jessica Fulton, PT, DPT, HFS,1 Kathryn Wright, PT, DPT,1 Margaret Kelly, PT, DPT, CSCS,1 Britanee Zebrosky, PT, DPT, CSCS,1 Matthew Zanis, PT, DPT, ATC, CSCS,1 Corey Drvol, PT, DPT,1 and Robert Butler, PT, PhD1

- Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014 Mar;34(2):129-33. Milewski MD1, Skaggs DL, Bishop GA, Pace JL, Ibrahim DA, Wren TA, Barzdukas A.

- Psychological predictors of injury among elite athletes S A Galambos1, P C Terry1, G M Moyle1, S A Locke1 BJSM 2005

- Therapeutic Neuroscience Education Louw 2013

- Mechanotransduction: Relevance to Physical Therapist Practice-Understanding Our Ability to Affect Genetic Expression Through Mechanical Forces. Phys Ther. 2016 May;96(5):712-21. Dunn SL1, Olmedo ML2.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). Squatting Kinematics and Kinetics and Their Application to Exercise Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3497–3506.

- Saraceni, N., Kent, P., Ng, L., Campbell, A., Straker, L., & O’Sullivan, P. (2019). To Flex or Not to Flex? Is There a Relationship Between Lumbar Spine Flexion During Lifting and Low Back Pain? A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 1–50.

- Nolan, D., O’Sullivan, K., Newton, C., Singh, G., & Smith, B. E. (2019). Are there differences in lifting technique between those with and without low back pain? A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 0(0).

- Mechanotransduction: Relevance to Physical Therapist Practice-Understanding Our Ability to Affect Genetic Expression Through Mechanical Forces. Phys Ther. 2016 May;96(5):712-21. doi:

- Owen, P. J., Miller, C. T., Mundell, N. L., Verswijveren, S. J., Tagliaferri, S. D., Brisby, H., … Belavy, D. L. (2019). Which specific modes of exercise training are most effective for treating low back pain? Network meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, bjsports–2019–100886.

- Lee, J.-S., & Kang, S.-J. (2016). The effects of strength exercise and walking on lumbar function, pain level, and body composition in chronic back pain patients. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 12(5), 463–470.

- Aasa, B., Berglund, L., Michaelson, P., & Aasa, U. (2015). Individualized Low-Load Motor Control Exercises and Education Versus a High-Load Lifting Exercise and Education to Improve Activity, Pain Intensity, and Physical Performance in Patients With Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 45(2), 77–85.

- Berglund, L., Aasa, B., Michaelson, P., & Aasa, U. (2017). Effects of Low-Load Motor Control Exercises and a High-Load Lifting Exercise on Lumbar Multifidus Thickness. SPINE, 42(15), E876–E882.

- Berglund, L., Aasa, B., Hellqvist, J., Michaelson, P., & Aasa, U. (2015). Which Patients With Low Back Pain Benefit From Deadlift Training? Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(7), 1803–1811.

- Steffens, D., Maher, C. G., Pereira, L. S. M., Stevens, M. L., Oliveira, V. C., Chapple, M., … Hancock, M. J. (2016). Prevention of Low Back Pain. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(2), 199.